TERC Blog

If it Has to Last, NASP

By Nickolay Hristov, Martha Merson, and Louise Allen

With Nathan Knox, Trent Spivey, Betsy Towns and Lexy Brunnert

Illustrations by Chris Tullar

Are you the one in any group or room who feels most responsible for expensive equipment? Are you at risk of being a nag when binoculars or microscopes are in use? Any place can be a hazard zone for equipment: sand in the desert, moisture in wetlands and swamps, grit in the city, fingerprints and grease in the lab. We’ve been to all of those places, and we’ve lived with fears of wrecked gear for years. Now we want to share our philosophy for keeping equipment and teams at their best: NASP.

Are you the one in any group or room who feels most responsible for expensive equipment? Are you at risk of being a nag when binoculars or microscopes are in use? Any place can be a hazard zone for equipment: sand in the desert, moisture in wetlands and swamps, grit in the city, fingerprints and grease in the lab. We’ve been to all of those places, and we’ve lived with fears of wrecked gear for years. Now we want to share our philosophy for keeping equipment and teams at their best: NASP.

If this is your first time seeing the term, the first three letters stand for “Not A Scratch.” Our solution to saving time, expense, and sanity began as a Protocol, then became something of a Policy, ultimately maturing into a Philosophy. NASP was first issued as a warning to assistants and students: Equipment should be handled with utmost care. As anyone who has tried knows, raising funds for equipment is not so easy to do. Once in hand, managing the bureaucracy associated with purchasing and maintenance contracts is a major time drain. Yet, in a single expedition, equipment can get trashed quickly.

NASP has been years in the making, growing and changing as we learned together, from our field sites on Maine’s coast, Texas’ Hill Country, California’s Sierras, and Mexico’s cloud forests, to our labs and studios in North Carolina, Massachusetts, and Maine. Prior to organizing research expeditions to remote caves in central Texas, we began a tradition of taking team members to a North Carolina pick-your-own strawberry field or cherry orchard. This low-key group activity built rapport among team members. As a bonus, it was the perfect place to emphasize gentle handling and careful packing. Once in Texas, both outside and inside caves, the team modeled meticulous care, preparing work sites and gear. The protocols prevented contamination of the fragile caves and preserved the delicate equipment that was essential to the work.

“Before joining the team, I’d heard lore, like stories of Tetris-style packing of equipment and a very meticulous protocol for equipment protection called the no-scratch policies [philosophy].” –LEXY

The NSF-funded Interpreters and Scientists Working on Our Parks (iSWOOP) project brought new players into the mix. iSWOOP supported rangers in national parks as they facilitated discussions with visitors about all the science going on behind the scenes. In professional development sessions at Carlsbad Caverns, Acadia, Indiana Dunes, and Joshua Tree National Parks, we demonstrated laser scanners and high-speed cameras with all of their many lights, lenses, cables, memory banks, and power supplies, all of which took hours to set up and break down. We spread out $200,000 of equipment and entrusted rangers to learn how to use it, collect data with us, and tell their audiences about it. And that was the point — the equipment was used with care, trust, and joy. During iSWOOP, we found that setting expectations for how rangers handled the equipment was key for sustaining our research capacity. Rangers, like our own team members, were quick to adopt the NASP mentality.

“NASP has slipped into our shared lingo. Lexy, doing yoga outside, sets her laptop on a towel instead of directly on the concrete: “Nathan, come see my NASPiness.” Parsimony is on our minds: Tying our shopping bags is easier than picking up spilled avocados, so says the law of parsimony. Parsimony is why we clean our boots and camping chairs before repacking them.”

— LEXY AND NATHAN

Over time, NASP practitioners found that introducing this idea in a light-hearted way worked better than issuing warnings or scolding a team member who had damaged equipment. NASP became somewhat subliminal, an idea that faded in the background, but one that affected everything from packing and unpacking equipment to walking through a biologically sensitive area. When a group took up NASP, it seemed to elevate everyone’s “game” by helping with focus, execution, and quality. This was a welcome effect: We worried less about working in difficult and dangerous conditions. We reduced falls and breakages to a minimum, and, with everyone’s senses more tuned, we sensed and spotted snakes and scorpions while avoiding their stings. NASP supported a culture of focus, care, and excellence, which we want to share with you through these five tenets:

#1 Know your gear.

Know how the components click, lock, and release, how they pack, and where they go. If you don’t know, a piece of gear can escape and land in the sand or get cracked on a rock. A backcountry expedition could come to a screeching halt with an expensive repair or replacement awaiting back home.

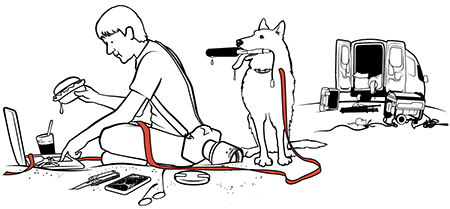

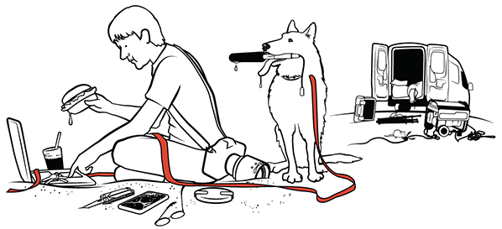

#2 Keep it clean.

Dry too! It’s better to never get your gear dirty or wet than to try getting it back to an impeccable condition. If you drop a lens bag in sand or water, it’s over. Furthermore, it’s ultimately simpler to always clean your gear after using it than sometimes cleaning and sometimes not. If you never clean your gear, it will require much more strenuous cleaning when it begins to malfunction.

#3 No hard on hard.

Two objects with hard surfaces should never touch each other. Invest in resealable zipper bags, cases, and soft drink koozies to keep hard surfaces from touching. If you keep hard surfaces from touching, you avoid scratches. Without scratches, things look and work like new — always!

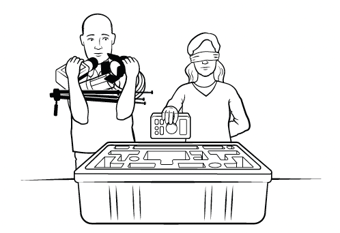

#4 Practice! NASP is for everyone.

Practice by setting achievable goals for yourself. “Not a scratch” can sound daunting at first, which is why we feel it’s important to say that NASP really isn’t so difficult. The more you practice, the more effortless and fun it becomes. Anyone who follows these tenets will find that NASP quickly becomes second nature. Get a friend on board too. NASP is not an exclusive club for people with special skills or a PhD. NASP is for anyone and everyone.

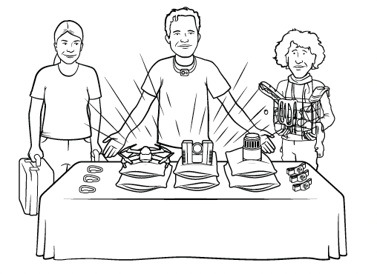

#5 Be parsimonious.

Be thrifty not just in terms of spending (as parsimonious implies in everyday usage) but take this idea of parsimony to its philosophical and scientific roots. In scientific circles, parsimonious means efficient and simple as well as economical. Check equipment before leaving, and make a backup plan. Keep movements simple to save time, save money, and save energy. The parsimonious individual, when presented with competing scenarios to similar outcomes, knows that the simplest one is preferred. Consider this: you just left Base Camp for a long drive to a field site before realizing that you forgot something that may or may not be important. It is simpler (and more parsimonious) to turn back and pick it up now than to risk realizing the forgotten item is critical and having to turn around later … if you even have time. In short, being parsimonious means keeping it simple to save time, save money, and save energy.

If you buy into our Not A Scratch Philosophy, you buy into a certain awareness that carries over into relationships with teammates and respect for people and places. From our team to yours, we hope that NASP can help you spend less time pestering about equipment and more time doing great work.

On my first expedition I learned that my role would be setting up unfamiliar equipment in the dark, on rocky terrain, under thousands of peeing bats. I decided to practice setting up and breaking down all the gear in the yard of the base camp. I did it twice. Was it overkill? Maybe. Did the NASP mindset pay off in a smooth shoot later? Absolutely.

—TRENT

Acknowledgements

iSWOOP is an NSF-funded project run by TERC PIs in collaboration with other educators, scientists, artists and designers. You can learn more about iSWOOP at https://www.terc.edu/projects/interpreters-and-scientists-working-on-our-parks/

iSWOOP Team

Our team members include: biologists like Georgina Dzikunu, Taylor Jones, Jenniffer Riley and Joe Lightsey, educators like Selene González, filmmakers like Chris Amodio, Raunak Kapoor and Jonathan Pfundstein, visual artists like Carrie Shaw and Andrew Mirmanesh, and designers like Dionysius Nikolaidis who explore new places and nagging questions with tools from diverse disciplines.

We call ourselves CATs (Coalition of Artisan Thinkers) and playfully invent a new language that adds an absurd number of consonants to everyday terms; it’s schpanqtastic. The team has articulated eight principles that guide our work and its expression via the arts. NASP is an outgrowth of that culture. For more on NASP, CATs, iSWOOP and TERC, see www.terc.edu/iswoop

Be a NASPer

Interested in starting your own NASP movement? Download the NASP poster at here.