TERC Blog

STORYBOOK STEM

Children’s Literature as a Tool for Supporting Equitable STEM Learning for Families

There is growing interest in supporting opportunities for STEM learning for families before children enter kindergarten. Such early learning experiences play an important role in preparing children for school and building lifelong STEM learning pathways (McClure et al., 2017; Shwe Hadani & Rood, 2018). In the preschool years, children’s storybooks are a common learning resource with huge potential to support STEM learning. They are also a primary way that many children learn about the world and engage in conversations with family members and other significant adults, even as the use of other media and technology increases (Common Sense Media, 2013; Geerdts et al., 2016).

Storybooks can be a powerful way of introducing or framing a STEM activity for young children and families.

Storybooks can be a powerful way of introducing or framing a STEM activity for young children and families.

Although the idea of combining storybooks and STEM education is not new, recently there has been a renewed and expanded interest in this area—especially as an approach to STEM access and learning in early childhood (Popov et al., 2017). A variety of projects across the country are now using fiction books and reading activities as avenues for STEM engagement with young children and families. However, there has been almost no coordination across these projects to ensure that their efforts build on prior work, align research questions, or share and synthesize results.

Storybook STEM was a National Science Foundation-funded conference grant led by TERC, in partnership with the University of Notre Dame, designed to foster this much needed collaboration and to better understand and advance research and education efforts. The project engaged school teachers, informal STEM educators, and researchers who work with or study family learning for preschool-age children (three to five years) and use early childhood fiction books as a tool to engage these families in STEM topics and skills. In this article, we share more about the project, recommendations that emerged through the discussions, and implications for how we support equitable learning for families.

Gathering Perspectives

Over two years, the Storybook STEM project team coordinated a series of activities to engage researchers and educators across the country and to gather information about current work. We collected feedback from 231 researchers, educators, and other professionals through a national survey, and we connected with 156 participants in an online forum. Such outreach allowed us to document how storybooks are currently being used (especially outside of school), the research base supporting this work, and outstanding questions that researchers and educators are grappling with.

Building on this foundation, in December 2019 our project team convened a group of 21 early childhood reading, family learning, and informal STEM education experts at TERC. Over two days together, we explored more deeply the role of children’s fiction books in supporting STEM learning with young children and their families and sought to catalyze cross-disciplinary thinking and partnerships. Participants came from across the country, representing a broad range of learning contexts, professional roles, audience focus areas, and STEM discipline expertise.

What Did We Learn?

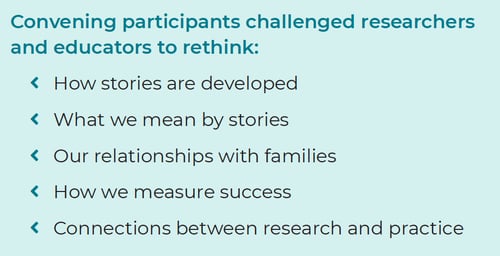

Through our discussions, the group developed a series of recommendations for researchers and educators, with a particular focus on the need to rethink and directly address issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion when integrating storybooks, STEM, and family learning.

1. RETHINK AND RECONFIGURE HOW STORYBOOKS ARE DEVELOPED

As several convening participants noted, the vast majority of children’s storybooks, whether they are explicitly related to STEM or not, are written and illustrated by White individuals and arguably represent White, middle-class values and cultural perspectives. Furthermore, the children’s publishing field is predominantly White, limiting the cultural perspectives shaping the development and selection of books (Kelly, 2018; Kliman, 2019).

In order to realize the potential of storybooks to broaden STEM access and engagement for families with young children, it is critical to increase the diversity represented in children’s books, as well as the teams that develop and study them. This means:

-

increasing the diversity of the individuals and contexts represented in these books so that children and families from all communities can see themselves in the stories;

-

ensuring that professionals of color are involved at every stage of story development, selection, distribution, and research; and

-

supporting senior professionals of color, including writers, illustrators, and researchers, to lead and bring their perspectives to the process.

This shift invites educators and researchers to reflect on the underlying issues power and privilege related to who selects and tells stories and who decides how these stories are integrated with STEM for families.

2. RETHINK AND BROADEN WHAT WE MEAN BY STORIES

From the outset, convening participants questioned the exclusive focus on storybooks rather than other forms of narrative and storytelling. Again, children’s storybooks are a common resource and component of home learning for White, middle-class families that may not be as common or as familiar for families from other communities. As convening participants discussed, a focus on storybooks must be balanced with supporting other family storytelling practices and finding creative ways to integrate these practices with STEM learning.

This broader approach includes empowering families to share and tell their own stories as part of STEM programs, which promises to:

-

create a deeper sense of relevance to the STEM topics for learners from many communities; and

-

put families in a central role for shaping the way story and STEM are integrated.

In general, convening participants stressed that we should not assume the same approaches, outcomes, and practices are appropriate for all communities. Ideally, educators, researchers, and families work together to understand and support the storytelling practices within each community and leverage these to create relevant and accessible entry points to STEM.

In December 2019, 21 experts were invited to TERC to explore the role of storybooks in supporting early childhood STEM learning.

In December 2019, 21 experts were invited to TERC to explore the role of storybooks in supporting early childhood STEM learning.

3. RETHINK AND EXTEND OUR RELATIONSHIPS WITH FAMILIES

Participants also stressed the importance of moving beyond thinking about families as solely the audience for programs that integrate children’s storybooks. Rather families should be invited in as collaborators at every step of the process, including:

-

identifying education and research goals;

-

prioritizing outcomes and measures;

-

creating or selecting stories to ensure representation of all storytelling traditions within different communities; and

-

implementing and studying programs.

This approach will not only help ensure that programs and research studies are relevant and accessible but will also put families in control of how stories become a resource for their children.

The re-orientation also implies embracing a different perspective on intergenerational learning and the multiple roles of parents. As emphasized by convening participants, parents are not just contextual factors in their children’s development but are educators and learners themselves. Programs for families that connect storybooks with STEM learning should therefore both support meaningful, enriching interactions between parents and children and further parents’ own learning about storybooks and STEM. Both research and educator efforts should also acknowledge the diverse approaches to parenting and family learning across cultures that influence how families engage with books and stories more broadly.

4. RETHINK AND EXPAND HOW WE MEASURE SUCCESS

Definitions of success guide our work as researchers and educators, and also reveal our biases and assumptions about storybooks, STEM, and education. Applying a diversity and equity lens to ideas about measuring success, the convening group explored ways that our outcome measures should be broadened and expanded. Different perspectives suggest a variety of approaches to this challenge.

-

From a disciplinary perspective, this might include emphasizing STEM practices just as much as content knowledge and vocabulary.

-

From a family learning and child development perspective, this requires thinking about ways that storybooks not only focus on STEM learning but also support and honor other family goals, such as early literacy development, cultural values, and spending time together.

-

From an equity perspective, educators and researchers should work closely with families and community stakeholders to decide what outcomes are of the highest priority and how existing family assets and strengths are highlighted and supported.

Participants acknowledged that this balancing act between different goals and perspectives is challenging but also critical to ensure that these efforts are successful for all communities.

Convening participants challenged the field to address issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion when integrating storybooks, STEM, and family learning.

Convening participants challenged the field to address issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion when integrating storybooks, STEM, and family learning.

5. RETHINK AND REINFORCE THE CONNECTION BETWEEN RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

Finally, convening participants agreed that more work needs to be done to connect researchers and practitioners at all stages of the process. This includes sharing the research that does exist with teachers, educators, and other professionals working directly with families and providing training and professional development opportunities on current questions, issues, and approaches related to using storybooks in STEM education. Similarly, practitioners can be engaged in the earliest stages of research and development to ensure that efforts are aligned with the needs of different professional audiences and incorporate insights from both research and direct experience with families. Overall, the participants felt that the cross-disciplinary nature of the convening should serve as a model for future efforts—catalyzing collaboration and communication across sectors, disciplines, and professional roles.

A Timely Call to Action

The Storybook STEM project brought experts together across disciplines, fields, and professional roles to better understand the work that has been done related to the integration of storybooks and STEM for young children and their families and to provide guidance for future research and educational efforts. What emerged from the convening is, we believe, something even more profound: a call to action for researchers and educators to think more critically about this integration and how it supports a vision of equity in STEM education for all communities.

This call to action is timely. It aligns with a growing movement across education and the STEM fields to move beyond superficial notions of access or representation and more fundamentally address the systems of oppression, inequity, and injustice that are ingrained within our society (Brown et al., 2019; Calabrese Barton & Tan, 2020; Garibay & Teasdale, 2019; Hall, 2020). We hope this convening and the recommendations that have emerged serve as one small contribution to these efforts.

Additional Resources

We invite you to explore project findings and resources in more detail on the project website, https://www.terc.edu/storybookstem

-

Full project report https://www.terc.edu/storybookstem/wp-content/ uploads/sites/5/2020/09/Storybook-STEM-Convening- Report-Final.pdf

-

Bios and resources from convening participants https://www.terc.edu/storybookstem/convening/convening-participants

-

List of resources compiled from the national survey and online forum https://www.terc.edu/storybookstem/resources

Download Hands On! Spring 2021

Acknowledgements

Storybook STEM is a collaboration between TERC and the Center for STEM Education at the University of Notre Dame. The project was funded through support from TERC and a grant from the National Science Foundation (DRL-1902536). Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders.

We are grateful to the many individuals that contributed their ideas and expertise to support this work. Special thanks to the steering committee that provided guidance and feedback throughout the project: Maureen Callanan, University of California, Santa Cruz; Laura Huerta Migus, Association of Children’s Museums; and Lauren Moreno, Catalysis, LCC. Thanks also to all the convening participants for generously sharing their time and expertise.

Authors

Scott Pattison, Ph.D., is a Research Scientist at TERC. He partners with communities to study and support STEM education, learning, and interest development in free-choice and out-of-school environments, including museums, community-based programs, and everyday settings.

Gina Svarovsky, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor of Practice at the University of Notre Dame Center for STEM Education. For nearly two decades, she has been interested in how young people, and especially those from traditionally underrepresented populations, learn science and engineering in both formal and informal learning environments.

Smirla Ramos-Montañez, Ph.D., is a researcher and evaluator at TERC, focused on culturally responsive studies related to informal STEM education. She has collaborated on a variety of projects with the goal of providing accessible, culturally relevant, and engaging experiences for diverse communities.

References

Brown, C. S., Mistry, R. S., & Yip, T. (2019). Moving from the margins to the mainstream: Equity and justice as key considerations for developmental science. Child Development Perspectives, 13(4), 235–240.

https://doi.org/10.1111/ cdep.12340

Calabrese Barton, A., & Tan, E. (2020). Beyond equity as inclusion: A framework of “rightful presence” for guiding justice-oriented studies in teaching and learning. Educational Researcher. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X20927363

Claud, E. (2000). Mother Goose asks “why?”: A family activity guide introducing science through great children’s literature. Vermont Center for the Book.

Common Sense Media. (2013). Zero to eight: Children’s media use in America 2013. Common Sense Media. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/ zero-to-eight-childrens-media-use-in-america-2013

Garibay, C., & Teasdale, R. M. (2019). Equity and evaluation in informal STEM education. New Directions for Evaluation, 2019(161), 87–106.

https://doi. org/10.1002/ev.20352

Geerdts, M. S., Van De Walle, G., & LoBue, V. (2016). Using animals to teach children biology: Exploring the use of biological explanations in children’s anthropomorphic storybooks. Early Education and Development, 27(8), 1237– 1249. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2016.1174052

Hall, J. N. (2020). The other side of inequality: Using standpoint theories to examine the privilege of the evaluation profession and individual evaluators. American Journal of Evaluation, 41(1), 20–33.

https://doi. org/10.1177/1098214019828485

Kelly, L. B. (2018). An analysis of award-winning science trade books for children: Who are the scientists, and what is science? Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 55(8), 1188–1210. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21447

Kliman, M. (2019). Storytelling math: Picture books as a vehicle for expanding views of math and who can do it. Hands On!, Fall 2019, 8–11.

McClure, E. R., Guernsey, L., Clements, D. H., Bales, S. N., Nichols, J., Kendall- Taylor, N., & Levine, M. H. (2017). STEM starts early: Grounding science, technology, engineering, and math education in early childhood. The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. http://www.joanganzcooneycenter.org/ publication/stem-starts-early/

Popov, V., Tinkler, T., Tore, A., & Meschen, C. (2017). The role of books and reading in STEM: An overview of the benefits for children and the opportunities to enhance the field. University of San Diego. https://stemnext.org/role-books-reading-stem/

Shwe Hadani, H., & Rood, E. (2018). The roots of STEM success: Changing early learning experiences to build lifelong thinking skills. Center for Childhood Creativity. http://centerforchildhoodcreativity.org/wp-content/uploads/ sites/2/2018/02/CCC_The_Roots_of_STEM_Early_Learning.pdf

.png)