TERC Blog

More Than Who's at the Table

Co-Designing a STEM-Based Virtual Reality Game with Neurodivergent Learners

When discussing diversity and inclusion, we often talk about changing who’s at the table, about making sure women, people of color, and other often-overlooked stakeholders are represented. The idea is that by expanding who is at the table, we’re expanding the voices being heard. This idea isn’t bad; indeed, it’s very important. However, this idea is also inadequate.

We need to be thinking not only about who’s at the table, but the entire nature of the table, what happens at that table, what resources and tools are available, and which voices are actually heard (or how ideas are shared in other ways).

Co-Design

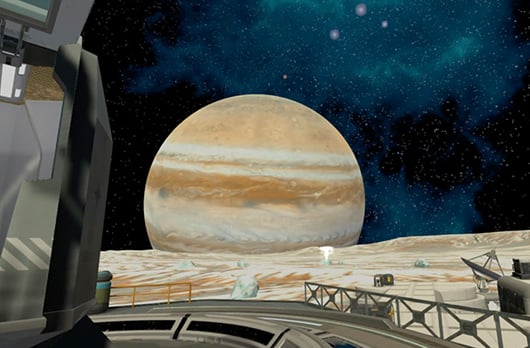

Just months into the COVID-19 lockdowns of 2020, the NSF AISL project UniVRsal Access: Broadening Participation in Informal STEM Learning for Autistic Learners and Others through Virtual Reality (DRL-2005447) was funded, with the goal of broadening participation in informal STEM learning by leveraging the unique affordances of VR for accessible and immersive science learning, designing for and with neurodivergent learners — learners with ADHD, autism, and other sensory, attention, and/or social differences. To achieve this, we embraced the neurodiversity movement’s tenent “nothing about us without us” (Charlton, 1998), and codesign dominated the first two years of the project.

Co-design is the act of designing and creating with stakeholders to ensure the final products are usable by and address the goals and needs of the stakeholders. Ten members of our co-design team were undergraduate interns from Landmark College, a post-secondary institute specifically for students who learn differently. Some of these interns were involved for a semester, others a year, and one for two years. The other four co-design team members were education developers and researchers from the Educational Gaming Environments group (EdGE) at TERC. Together, we shaped the STEM-based VR game Europa Prime and related research.

.jpg?width=500&height=330&name=KATHERINE-HODER-(LANDMARK-INTERN).jpg)

Scaffolding

All the co-design team members had “a seat at the table,” but this alone wasn’t going to translate into everyone’s ideas being “heard.” While none of our neurodivergent co-design team members were non-verbal, there were definitely different levels of comfort, willingness, and ability with sharing ideas verbally. Thus, meetings had to be carefully crafted to meet the preferences and needs of the participants as a team and as individuals. For example:

- Miro boards were used for brainstorming, feedback, and more. A specific question would be asked; everyone would generate ideas simultaneously, capturing them in just a few words; everyone would consider all the ideas without judgment, marking ones they liked, had questions about, or otherwise wanted to revisit; and only then would ideas be discussed.

- Each team member was regularly called upon by name, so everyone had opportunities to share. We put unique scaffolds in place to facilitate different individuals. Some members had a hard time talking when put on the spot, so back-channel communication via Chat was employed (e.g., “As soon as ___ is done, I’m going to call on you. Is that alright? Want to share about your ___ or __ idea?”)to give them time to gather their thoughts and not be taken by surprise. One member simply didn’t want to talk some days, and that was accepted. Some members were perfectly comfortable talking, so their scaffolds related to distilling what they wanted to say as well as building awareness of when to give others a chance to speak.

- Specific options for in-meeting engagement were identified and implemented. For example, one team member explained they didn’t feel a need to speak up if they agreed with what was being discussed. Since we didn’t want to lose the vital information of agreement, the use of “agree” or a thumbs-up emoji in Chat was implemented and reinforced as a deliberate, predetermined means of sharing.

- Time and space were always given for being “off topic.” One team member noted how important it was that the co-design process just “rolled with it” when they became distracted or rambled on a tangent. Such behavior had previously been treated as a problem or something to be curtailed; now it was being treated as an asset. It was important for team building, but also, interesting ideas often came up during these tangents or they were turned into opportunities to think about how the game could — and should — respond to players who were pursuing unintended directions.

Many other scaffolds were used during and between meetings. None of these scaffolds were, in and of itself, all that innovative—task templates can be useful, audio recordings are an alternative to writing, assignment descriptions can be highly specific or loose guidelines, drawings or online images can be used to capture ideas, and partners can assist each other. To facilitate co-design, the team put extra intentionality into finding and supporting different ways for each and every member to fully participate and help shape what was being developed. And more than any specific scaffold, co-design is about building relationships and trust.

.jpg?width=500&height=267&name=STEPHEN-SOLTERO-(LANDMARK-INTERN).jpg)

Reshaping

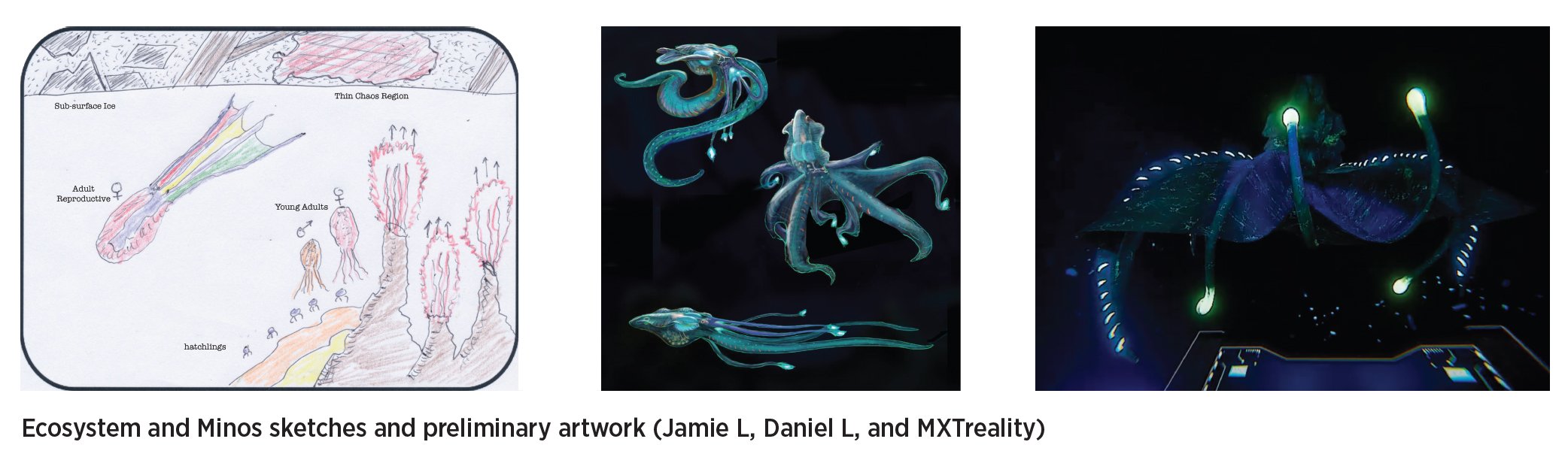

As part of a previous pilot project, some basic elements of Europa Prime had been developed and tested. Co-design team members largely embraced these pre-established elements; however, they also offered and pursued ideas for significant story alterations, backstory and character development, physical game controls, and more, reshaping the game in unexpected ways important to them. Sometimes these contributions were distinct from obvious neurodiversity considerations, such as with the design of the fictional Flame Jelly lifeforms introduced by a member interested in biology and animal behavior. Others struck to the heart of addressing the goals and needs of neurodivergent learners.

For example, several co-design team members proposed EM Spectrum puzzles as good STEM content with important sensory-input scaffolding connections. As the design process progressed, we saw that perceiving different wavelengths of EM radiation, including ones beyond the visible, could be analogous to challenges faced by some neurodivergent learners when sensory input is overwhelming, inaccessible, and/or incomprehensible. Also, as the team faced and addressed its own communication-related challenges, members used this experience to motivate the idea of integrating communication into the game. The need to figure out how to communicate across various divides became an ingame means of addressing social differences.

Bringing together these and other design ideas, the team devised and crafted the Minos, fictional cephalopod-like aliens who communicate using the EM spectrum, but only at very low brightness levels (as bright lights can overwhelm) and only partially in the (so-called) visible (as perceptions can differ). The Minos communicate by flashing sequences of different colors, including in ultraviolet wavelengths. Just as learners with autism may experience sensory integration differently than (so-called) neurotypical learners, the player and the fictional Minos are receptive to different sensory input and must find common understandings and establish basic levels of communication. And this is just one example of how the codesign team has addressed fundamental aspects of the proposed project—STEM learning, sensory differences, and social scaffolding—in ways that wouldn’t have come about without the central involvement of neurodivergent members of the team.

Conclusion

Engaging in authentic co-design requires:

- Listening with empathy

- Treating team members as whole people, not just whatever “got them” their seat at the table

- Learning what each individual needs/wants to comfortably share ideas… and then implementing

- Providing EVERYONE with multiple ways of capturing ideas

- Allowing for naturally generated team building

- Using names — calling on people and crediting people

- Planning and scaffolding all meetings and tasks carefully

- Building in time for distraction and tangents; this isn’t wasted time

- Practicing patience and open-mindedness as plans take detours and change course

- Building relationships and trust

- Taking risks and (for leaders) giving up (full) control

Doing this can be challenging and time consuming, but it’s worth it, as co-design has the potential to be transformative. What’s happening at your table? Check out more about co-design, the project, and the transition from design to development at edge.terc.edu and https://www.terc.edu/projects/univrsal-access/

Acknowledgements

UniVRsal Access co-design team: Zachary Alstad (EdGE), Gerald Belton (Landmark), Ibrahim Dahlstrom-Hakki (EdGE), Teon Edwards (EdGE), Ian Hagberg (Landmark), Katherine Hoder (Landmark), Jamie Larsen (EdGE), Daniel Lougen (Landmark), Nicholas Payne (Landmark), Daniel Santana (Landmark), Becky Scheff (Landmark), Stephen Soltero (Landmark), Ben Stafeil (Landmark), and Zack Steinbaum (Landmark), as well as Bennett Attaway (observer from Knology, the project’s external evaluators)

Author

Teon Edwards is co-founder and director of design for EdGE at TERC. With a background in astrophysics, mathematics, and education with a focus on the use of technology and multimedia for learning, she has developed numerous science curricula, experiences, tools, and games. She’s PI of the UniVRsal Access project.

References

Charlton, J. M. (1998). Nothing about us without us: Disability oppression and empowerment. Berkeley, Calif: University of California.

NSF

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. DRL- 2005447. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

.png)