TERC Blog

The Double Bind in Physics Education: An Exploration of Inclusion in Physics

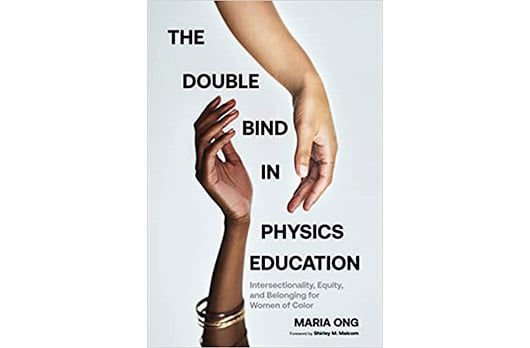

Maria (Mia) Ong’s groundbreaking book, The Double Bind in Physics Education, presents a compelling case for far-reaching higher education reform. Her extensive 25 years of research sheds light on the challenges faced by women of color in STEM fields, documenting 10 women’s experiences from entrance into undergraduate physics programs to their educational and career journeys.

Dr. Mia Ong is a Senior Research Scientist at TERC and leads the Institute for Meta-Synthesis. She is also the Founder and Director of Project SEED (Science and Engineering Equity and Diversity), a social justice collaborative affiliated with The Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles at UCLA. For over 20 years, Dr. Ong has conducted qualitative and mixed-methods research, including three NSF-sponsored literature synthesis projects, focused on equity in STEM. Her publications include synthesis articles on women of color in STEM in Harvard Educational Review and Journal of Engineering Education. She has extensive experience teaching qualitative research methods and equity in education at schools such as Harvard, Vanderbilt, MIT, Boston University, and Swarthmore College. Dr. Ong holds a doctorate in Social and Cultural Studies in Education from the University of California at Berkeley.

To gain further insights into her work, we had the opportunity to sit down with Maria Ong for an interview. In this conversation, she discusses the challenges these women face, the intersectionality of race and gender discrimination, and how it influences academic opportunities and career choices.

CAN YOU SHARE THE STORY BEHIND WHY YOU FELT COMPELLED TO WRITE THIS BOOK?

The short answer is that I wanted to write a book that addressed the question: Why haven't diversity efforts from the past 2+ decades worked? Millions of dollars have been spent on efforts such as summer STEM camps for middle and high school students or teaching undergraduate students' self-confidence or behaviors rooted in grit. These efforts are admirable and well-intended, but they're insufficient in scale and band-aids to a much bigger problem. It became clear to me that the practices and culture within STEM institutions were the underlying issues.

IF THERE'S A SHORT ANSWER, IS THERE ALSO A LONG ANSWER?

When I was a graduate student in the mid 90s, I became interested in the experiences of intersectionality, specifically the experiences of women of color, in spaces that were not traditionally built for them. By "women of color" I mean women who identify as Black, African American, Latinx or Latine, Chicana, Native American, Indigenous, Asian American, mixed race or ethnicity. As an Asian American woman and a former chemistry major, I was drawn to the sciences and attracted to physics as a context to study. Prior to doing my study, I had a brief role as a coordinator of a physics undergraduate program. I noticed many women of color had similar stories and experiences, yet they were not communicating with each other about them. I started searching for existing research that could shed light on what I was observing. Surprisingly, I discovered that there was very little research available on the topic. At that point, a colleague suggested I take the initiative and conduct the research myself. I made the decision to leave my position and embark on this research journey that ultimately culminated in this book.

COULD YOU SHARE THE BEGINNINGS OF YOUR RESEARCH PROCESS AND HOW IT EVOLVED?

The research began with a simple set of questions: What is it like to be a woman of color in physics or physics-related fields? What drove women of color to pursue degrees in these fields? What were the barriers? What supported them along the way? I began to follow a small group of women of color, as well as other nontraditional students. They generously allowed me to study them over the years, observing them in classrooms, homes, and eventually, in workspaces. Along the way, I conducted numerous interviews to delve deeper into their experiences. Their stories over the past 25 years, I thought, gave deep insight into why the representation of women of color in physics hasn't significantly changed in the past few decades.

Mia Ong visited a simulated surface of Mars at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory during a data collection trip (February 1997).

HOW DID YOU ARRIVE AT THE TITLE FOR YOUR BOOK?

When I started the research for this book the concept of intersectionality was not very well studied or very well understood, especially within STEM education contexts. Dr. Shirley Malcolm and her colleagues Paula Hall and Janet Brown had written a very important report called, "The Double Bind: The Price of Being a Minority Woman in Science." It was published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1976 and addressed the experience of being a woman of color in science, but the phenomenon of intersectionality in STEM wasn't well publicized beyond this report. Of course, their report had a tremendous impact on all my research, and the title of my book honors their report.

WHO DO YOU ANTICIPATE WILL BE THE IDEAL AUDIENCE FOR THIS BOOK?

I wrote this book for young women of color and individuals belonging to other marginalized groups who are pursuing careers in physics and other STEM fields. I hope it also engages faculty and leaders at both local and national levels, as well as researchers.

CAN YOU ELABORATE ON THE IMPACT YOU ENVISION FOR EACH OF THE THREE AUDIENCES THIS BOOK SPEAKS TO?

My ideal outcome is that this book provides support and validation to women of color who may have felt alone or doubted their experiences. I want them to know that they belong, that what they are going through is real, and that they are not alone. I hope discussions of this book create spaces where people can openly share their experiences and find inspiration in knowing that others have succeeded despite the odds. I envision this book reaching people in positions of power who are looking for guidance on creating change for inclusive excellence. In the book I present a framework that offers a variety of options, ranging from small adjustments to syllabi to more substantial interventions, all of which can profoundly impact individuals' sense of belonging. For other educators and administrators, I hope that it opens their eyes to the stories and challenges highlighted. Ideally, I hope it will encourage them to recognize that these experiences are not limited to specific classrooms or universities, and that they can make meaningful changes in their own environments.

Lastly, it would be wonderful if this book sparks further research. There are still many unanswered questions and gaps in our understanding. By presenting these unanswered questions, I hope to inspire other researchers to delve into these areas and gather the necessary data to find answers. There is much work to be done, and I believe that this book can motivate researchers to explore and address these important issues.

ARE THERE ANY SPECIFIC CHAPTERS/ PASSAGES THAT YOU THINK ARE PARTICULARLY COMPELLING TO SHARE, AS AN ENTRY-POINT TO READING THE ENTIRE BOOK?

I used mainly storytelling in this book because stories are accessible. They reach peoples' hearts to create change in a way that intellectual arguments can't always do. I also used theory to frame the stories, to give readers a shared vocabulary and theoretical basis, and to demonstrate that these concepts have been studied in the past, though not necessarily with women of color or in the field of physics. Irene's story reveals how her classmates overlook her expertise when they go to the man she's tutoring for answers rather than her, demonstrating concepts of invisibility and lack of recognition. Kendra encounters discrimination when her access to a science building is questioned by a security guard even though she had a key, which illustrates acts of low expectations and stereotyping on the part of the guard. And Elena faces accusations of cheating after doing well on an exam because she was given more time due to a learning difference, which is an example of identity-based harassment. These individual stories collectively contribute to a deeper understanding of the experiences and challenges faced by women of color in physics and related fields.

WHAT IS YOUR IDEAL OUTCOME WITH THE RELEASE OF THIS BOOK?

I have a few ideal outcomes: an increase in women of color and other members of minoritized groups in physics and related fields, a greater sense of belonging for them, an awareness by leaders, faculty, and students alike of intersectionality and how it plays out in physics and other STEM spaces, and systemic change resulting in greater inclusion overall.

WHAT'S NEXT, IF ANYTHING, IN THIS LINE OF RESEARCH?

It can be challenging to secure funding for this type of work, but I would love to continue this line of research. Over the past 25 years, I have been a constant presence in the lives of the women featured in this book. They have shared their milestones and personal achievements with me, whether it's getting promoted, graduating, starting a family, or even celebrating their children's successes in a soccer game. I don't take this lightly and I'm honored to be this person in their lives. It's incredibly inspiring to witness many of these women now holding positions of power and influence. They are actively contemplating and implementing changes to ensure that the next generation does not have to face the same obstacles they encountered. They are invested in grooming future leaders who can drive even more significant transformations in our field. So, yes, there is a desire to carry forward this research and explore the continued growth and impact of these women in shaping the future.

CREDITS

The Double Bind: The Problem of Being a Minority Woman in Science: The Problem of Being a Minority Woman in Science is published by Harvard Educational Press and avaialble for purchase at https://qr.page/g/DMqS1jCdq8

The book draws its title from the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) publication, The Double Bind: The Problem of Being a Minority Woman in Science [authored by Shirley M. Malcom, Paula Q. Hall, and Janet W. Brown], in which the status and experiences of women of color in STEM was first raised. The "double bind" referred to the unique challenges minority women faced as they simultaneously experienced sexism and racism in the STEM careers.

Photos courtesy of M. Ong.

-Bonda.jpg)

.png)